Unlike fine wines and some types of cheeses, not everything ages well. Such is the case with the materials used as insulation of electrical wiring. While the copper metal used as the conductor in many wire types will last virtually forever, the cladding used to protect and insulate the wire allowing electrons to flow to their final destination does not.

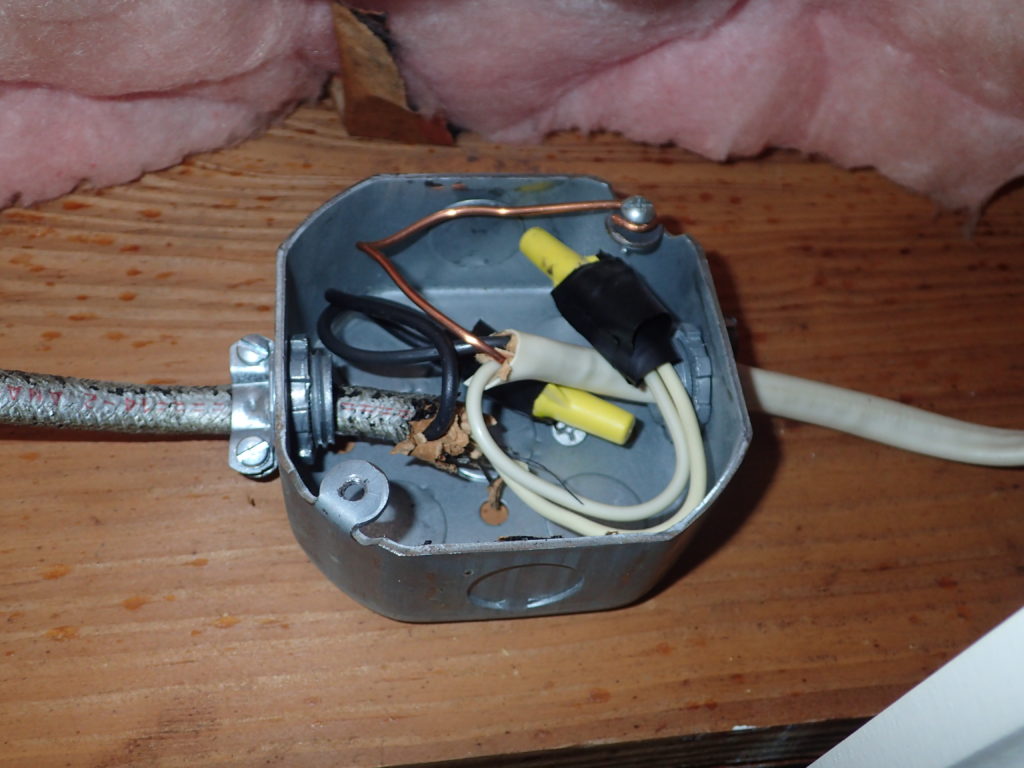

The branch wiring in a typical residence is installed using nonmetallic cable assemblies. This wiring, known as NM-cable, is a composition of conductors, usually copper, clad in an insulating material. In today’s technology, a group of either two or three of these clad conductors is assembled with a bare metal ground conductor with a paper spacer and then encased in a plastic jacket.

A view of typical, modern-day NM-B cable assemblies. The color of the outer jacket depicts the size of the conductors within.

While the assembly of this cable type has remained constant since it was created in 1922 by the Rome Wire company, the materials used in its construction have changed. The first iteration of the NM cable was made of rubber insulated conductors with a woven cloth outer jacket. No ground conductor was present in the first version. Later, a smaller gauge bare ground conductor was added to the assembly. In the 1960s the insulation was changed to a thermoplastic material instead of rubber. In 1984 a change was made to the makeup of the thermoplastic material giving the cable a 90 degrees Celsius operating temperature limit, up from 60 degrees Celsius for the prior version. The increased temperature version of the cable assembly gained the designation NM-B.

The original rubber clad insulation had problems. Oxygen in the air would attack the rubber and deteriorate it, making it brittle. Movement of the cable, whether it be from thermal expansion or making new connections to the older wires, would cause loss of the insulation as it crumbled away. Over time the loss could cause shorts to other conductors or surrounding components, cause circuit breakers to trip or fuses to blow as well as presenting a fire hazard. The newer thermoplastic materials do not have the same response to the oxygen in the air, making them last longer. However, repeated exposure to heat and cold causes these materials to become brittle as well over time. Exposure to heat from a fire in a structure can also effect the integrity of the insulation.

Many studies been done on the expected life of NM cable assemblies. The newer NM-B assemblies have been found to have an expected service life of 25 to 40 years while the older NM cables had an expected life of 20-25 years. Factors such as high temperatures and moisture levels can have a degrading effect on the integrity of the insulating materials.

Straightforward testing methods exist to evaluate the integrity of an installed cable assembly. A measure of the insulation resistance of a cable while in place can be made with some limited preparation. The values of the insulation may range from a few gigaohms for a brand-new cable with no installation defects to a few megaohms for a 30-year-old cable in a typical installation. Standards exist to interpret these insulation resistance values for the given application of the cable assemblies being tested.

Tom Kelly has a Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering and a Master of Science in Electrical Engineering from Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Florida, along with a Master of Business Administration with emphasis in strategic leadership from Winthrop University, Rock Hill, South Carolina. Tom’s 30-year career in electrical engineering includes forensic engineering investigations involving industrial electrical accidents, electrical equipment failure analysis, control system failures, robotics and automation components, and scope of damage assessments. He has conducted investigations for fires, arc flash incidents, electrocution and electric shock accidents and lightning strike evaluations.