“Was a dark stormy night as the train rattled on…” Anybody? 1985? Scarecrow? Come on… this was when Cougar was still a Mellencamp! Ok… it was called Grandma’s Theme… you’ll have to look that one up… but as I sat down to write this blog on the environment, that song kept running though my head. If you look it up, it will have a similar effect… just a little warning.

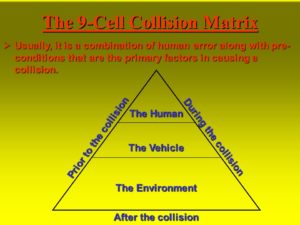

In our last installment of the 9-Cell Collision Matrix let’s travel down the wet, slippery slope of environmental factors that can contribute to car crashes, and maybe take a closer look at the things around us, at or near our crash scene that may reveal some important clues.

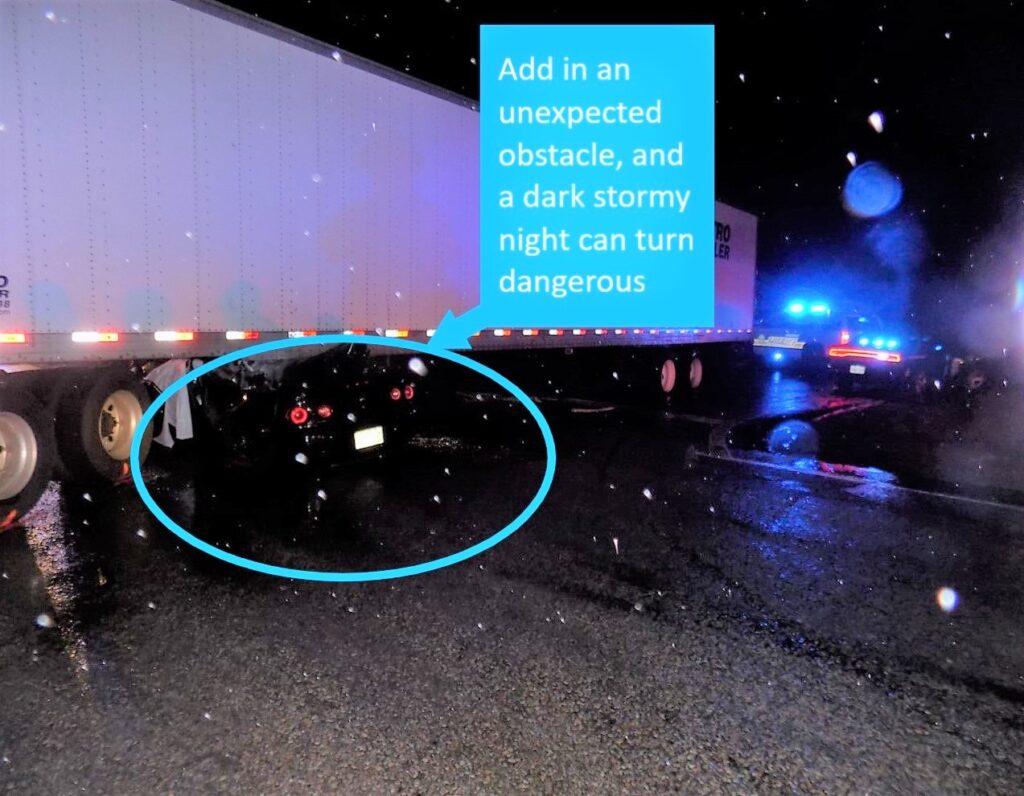

Photo by Mark Turner

We’ll start with the most obvious environmental factor, weather. A wet roadway surface is a slippery roadway surface. The oily, greasy bituminous material comprised in an asphalt roadway mixes with standing water to create the perfect receipt for car crashes. Of course, ice and snow on the road surface takes the slippery wet roadway to a whole new level. What about sand or loose gravel on the road? All of these create a lesser friction value than is afforded to us by a normal dry roadway surface and in turn causes a longer stopping distance for your vehicle. Fine for normal stopping, but what if a scenario arises where emergency braking is required? Like maybe the car in front of you slams on the brakes or a child darts in front of you chasing a ball into the street. When we are not able to achieve the full friction value of the roadway surface due to weather, we must change our tactics. That same following distance from the car in front of you that works just fine on a clear day will no longer work on a wet roadway. That same level of vigilance we use on a crowded neighborhood street on a clear day will no longer work on a rainy day.

Any form of precipitation also affects the driver’s sight distance, which in turn affects the driver’s perception and response time (remember our old friend PRT?). Problem is, we as drivers must first recognize and define shape, size, direction of travel, and several other factors of a potential hazard before PRT even begins. Would a rainy, foggy day make defining that hazard more difficult? You bet it would! Remember the car is rolling while the hazard recognition process is taking place, sometimes rolling fast. 55 miles per hour is 80.63 feet per second. Imagine that normally a driver could discern and react to a hazard in 2 seconds under ideal conditions. That means they’d need to react at about 161 feet away to avoid it. That same driver may now need twice that amount of time, if the weather has taken a bad turn, so now we’re talking a distance of about 322 feet, and you haven’t even touched the brake pedal. Remember, the road is wet, can we stop as fast as normal when we do get around to pressing the brake pedal? No, we need even more space to avoid the hazard. Scary stuff indeed!

Nighttime is the right time… to be with the one you love? Yes. To be able to see and recognize a potential hazard? well… No. As the sun goes down, so does our ability to distinguish the conspicuity of objects around us. Other vehicles, pedestrians, terrain features, roadway layout, roadway signage, just to name a few, are more difficult to recognize at night. A lack of ambient lighting can also make discerning distance more difficult as well. You may indeed see something, but just what it exactly is and how far away, may prove to be difficult to distinguish. Remember from our last paragraph, the car is moving while the brain is thinking, sometimes fast right? We just don’t have a lot of time for the decision-making process while driving and an environmental factor such as a dark stormy night certainly diminishes our already frail abilities.

Now that we’ve considered how the environmental factors of weather and darkness play a role in car crashes, let’s take a closer look at the terrain around us.

As you pull up to the stop sign at the intersection right below your house, as you’ve done a thousand times before, you look right, look left, and then back right again, and there is nothing coming… only there is. You know, very well that there is a steep hill a couple hundred feet to your left, but the speed limit for the intersection is 35 miles per hour, and there was no car there only a second or two ago, but as you pull slowly from the stop sign, the left front of your vehicle is violently smashed by another car. As you are now being triaged in the local emergency room, the State Trooper walks in and asks you what happened in the wreck… I have no idea, you say. Then the Trooper hands you an insurance form to turn in and most likely a ticket for failure to yield the right of way. But how can that be, you think to yourself. There was nothing coming when I pulled out! The good news is, I can help! After an inspection and airbag control module imaging of the vehicle that struck you, it is determined that the vehicle was traveling 82 miles per hour in the 35 mile per hour intersection. In addition, time and distance calculations reveal that the vehicle would have been invisible to you as you began to enter the intersection. Time and distance calculations further reveal that had the vehicle that struck you been traveling at the posted speed limit; your vehicle would have been completely through and on the other side of the intersection when the striking vehicle arrived at the original impact location. Armed with the information provided in the collision reconstruction, the failure to yield charges against you were dismissed and the speeding vehicle was shown as the contributor in the collision.

Environmental factors are always at play as we navigate the highways and byways of motorized travel, whether it’s the ones mentioned above, or many others, they can and do influence car wrecks in many unique ways prior to, during, and after the collision.

Mark Turner, ACTAR #2368, is a vehicle collision reconstructionist with Warren. Prior to joining Warren, he worked for 25 years as a South Carolina Highway Patrol Trooper including 10 years as a Multi-Disciplinary Accident Investigation Team (M.A.I.T.) leader (corporal). Mark is accredited as a Traffic Accident Reconstructionist by The Accreditation Commission for Traffic Accident Reconstruction (ACTAR). He investigated in excess of 900 vehicle accidents and incidents as a trooper. Then, as a member of M.A.I.T. for 10 years, he was involved in over 1000 detailed investigations and collision reconstructions. Mark has testified multiple times in state courts and has been court qualified as an expert in accident investigation and collision reconstruction. Mark is a member of the South Carolina Association of Reconstruction Specialists (SCARS), the International Association of Accident Reconstruction Specialists (IAARS), and the National Association of Professional Accident Reconstructionist (NAPARS). He completed the Law Enforcement Basic Program at the South Carolina Criminal Justice Academy in Columbia, South Carolina.